Abstract

For my thesis project, I will look into the human action of preservation, digging into it through different layers of analysis and interpretation. The scope of my investigationrevolves around three aspects of preservation: Who is preserving? What is preserved? Why preserve? And since humans are the subject of this action, it will be examined through three scopes: human as individual, human as community and human as species. In response to different aspects of preservation, my methods will include interviews, cultural probes and video-ethnography on individuals and culture groups. Mystudio explorations will take a diagrammatic form, including visualizations of datas I collect from interviews and cultural probes. Instead of aiming for absolute answers, I would like them to serve an enlightening purpose for me and the audience to continue investigating and contemplating on preservation in terms of its meaning, potential, and relationship to ourselves and the society.

Written Description

For my thesis project, I will look into the human action of preservation, digging into it through different layers of analysis and interpretation. What are we preserving? Why does preservation matter? What if we quit preserving? Human, as the subject of this action, will be examined through three scopes: human as individual, human as community and human as species.

On an individual level, preservation could be interpreted as keeping, not disposing of something. Human’s possession of objects bridges ourselves and the material world. It contributes to building a continuity of self as well as a tangible connection to our past memories and experiences. When possession extends to collection, an enclosed personal space is created which protects the collector from all external norms and powers. By collecting, people preserve their memory, experience and identity.

On a community level, people from a culture collectively construct their history through preservation of certain historical objects and events. The Jewish Museum, for example, is dedicated to the enjoyment, understanding, and preservation of the artistic and cultural heritage of the Jewish people through its collections. Preservation here serves as not only a memorial of the past, but also extends to the future and shows responsibility towards future generations.

When considering humans as a species, we preserve other species on the earth in order to prevent them from extinction. By making and collecting animal specimens as a way of preservation, are humans essentially depriving other species of life for the sake of human needs? In this sense, preservation is an exercise of human power over other species and against the natural order of ephemerality. This phenomenon also leads me to question whether preservation is necessary in some circumstances. In other words, is decay always bad? Is there something that is made for decay or not preserved?

On an individual level, preservation could be interpreted as keeping, not disposing of something. Human’s possession of objects bridges ourselves and the material world. It contributes to building a continuity of self as well as a tangible connection to our past memories and experiences. When possession extends to collection, an enclosed personal space is created which protects the collector from all external norms and powers. By collecting, people preserve their memory, experience and identity.

On a community level, people from a culture collectively construct their history through preservation of certain historical objects and events. The Jewish Museum, for example, is dedicated to the enjoyment, understanding, and preservation of the artistic and cultural heritage of the Jewish people through its collections. Preservation here serves as not only a memorial of the past, but also extends to the future and shows responsibility towards future generations.

When considering humans as a species, we preserve other species on the earth in order to prevent them from extinction. By making and collecting animal specimens as a way of preservation, are humans essentially depriving other species of life for the sake of human needs? In this sense, preservation is an exercise of human power over other species and against the natural order of ephemerality. This phenomenon also leads me to question whether preservation is necessary in some circumstances. In other words, is decay always bad? Is there something that is made for decay or not preserved?

Studio Explorations

For my studio explorations, I would like to delve into preservation as consolidating memories as my first deliverable, by conducting a fair amount of unstructured interviews as well as cultural probe activities that enable participants to contemplate on their

relationship between their possessions. Based on what I get from the interview and cultural probes, I would like to visualize and construct a personal space by reassembling the fragmental experience behind each collected object. It will take a more diagrammatic form, mapping out the connection between past and present,

ourselves and the material world and maybe also form some kind of narrative. My next exploration will be in response to preservation as constructing history. I would like to look into this time of digital dark age through a visual-ethnography, capturing our

current engagement in the digital world as a society. The result will be a collective

archive as a preservation of a socially constructed history during this digital dark age. It will be taking place both in digital and physical form, extending to an exploration of the meaning of decay in the digital and physical world.

archive as a preservation of a socially constructed history during this digital dark age. It will be taking place both in digital and physical form, extending to an exploration of the meaning of decay in the digital and physical world.

Mapping

Precedential projects

Grosse Fatigue, 2013

Camille Henrot

Grosse Fatigue considers the museum’s restless accumulation of objects and dead animal specimens—often achieved through forms of violence, like genocide, extinction, and environmental damage—that feeds our infinite hunger for knowledge. If vanity has compelled us to construct our own history through forms of possession and death, Henrot considers the underlying impulses that continue to drive new technologies and the seduction of constructing ourselves online.

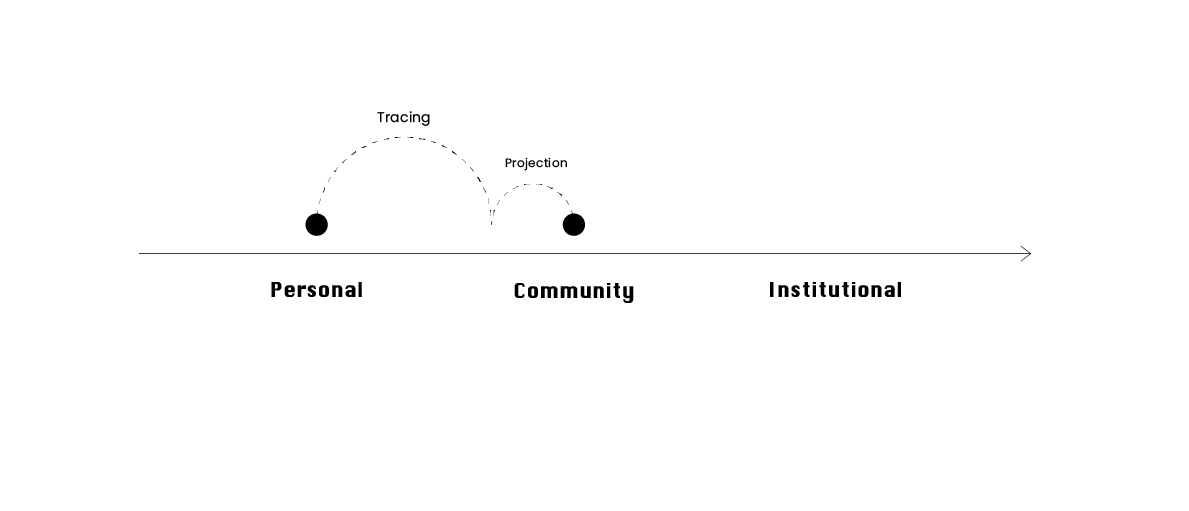

<PROJECTION>

Interspecies Futures [IF] , 2021

Curated by Oscar Salguero

[IF] is the first survey of bookworks by leading international practitioners from the contemporary fields of bio-art and speculative design who have turned to the book as a tool for the proposal of alternative human-nonhuman scenarios.It introduces practices that cover a large range of positions toward the nonhuman, and propose new eco-conscious alternatives. Some of the practices also imply trans-species dreams.

Digital Colonialism, 2016-2019

Morehshin Allahyari

Since 2016, Allahyari has advanced the concept of digital colonialism to characterize the tendency for information technologies to be deployed in ways that reproduce colonial power relations. This performance focuses on the 3D scanner, which is widely used by archaeologists to capture detailed data about physical artifacts, considering how these narratives intersect materially and poetically and how they may be resituated and rewritten.

<TRACING>

Le Pain Symbiotique, 2014

Anicka Yi

Employing materials such as soaps, potato chips, milk, and hair gel, Anicka Yi creates tactile and fragrant sculptures, paintings, and installations that play on the paradox between the enduring, timelessness of art, and ideas of impermanence. “I'm interested in connections between materials and materialism, states of perishability and their relationship to meaning and value, consumerist digestion and cultural metabolism,” she says.

<TRACING & PROJECTION>

To be Preserved without scandal and corruption , 2020

Gabriel Rico

This work is characterized by the interrelation of seemingly disparate objects. Self-proclaimed “ontologist with a heuristic methodology,” Gabriel Rico pairs found, collected, and manufactured materials to create sculptures that invite viewers to reflect on the relationship between humans and our natural environment.

<TRACING>

Beijing Preservation, 2003

OMA

> The dilemma: building is less permanent in Asia and restoration often leads to a harsh reconstruction from zero that removes all traces of authenticity in favor of rigid, bloated rebuilding. In the name of preservation, the past is made unrecognizable.

> The most visionary approach to preservation would be to use it in a prospective rather than retrospective way by declaring different areas of the city to be preserved for different periods of time.

<PROJECTION & INTERVENTION>

Camille Henrot

Grosse Fatigue considers the museum’s restless accumulation of objects and dead animal specimens—often achieved through forms of violence, like genocide, extinction, and environmental damage—that feeds our infinite hunger for knowledge. If vanity has compelled us to construct our own history through forms of possession and death, Henrot considers the underlying impulses that continue to drive new technologies and the seduction of constructing ourselves online.

<PROJECTION>

Interspecies Futures [IF] , 2021

Curated by Oscar Salguero

[IF] is the first survey of bookworks by leading international practitioners from the contemporary fields of bio-art and speculative design who have turned to the book as a tool for the proposal of alternative human-nonhuman scenarios.It introduces practices that cover a large range of positions toward the nonhuman, and propose new eco-conscious alternatives. Some of the practices also imply trans-species dreams.

Digital Colonialism, 2016-2019

Morehshin Allahyari

Since 2016, Allahyari has advanced the concept of digital colonialism to characterize the tendency for information technologies to be deployed in ways that reproduce colonial power relations. This performance focuses on the 3D scanner, which is widely used by archaeologists to capture detailed data about physical artifacts, considering how these narratives intersect materially and poetically and how they may be resituated and rewritten.

<TRACING>

Le Pain Symbiotique, 2014

Anicka Yi

Employing materials such as soaps, potato chips, milk, and hair gel, Anicka Yi creates tactile and fragrant sculptures, paintings, and installations that play on the paradox between the enduring, timelessness of art, and ideas of impermanence. “I'm interested in connections between materials and materialism, states of perishability and their relationship to meaning and value, consumerist digestion and cultural metabolism,” she says.

<TRACING & PROJECTION>

To be Preserved without scandal and corruption , 2020

Gabriel Rico

This work is characterized by the interrelation of seemingly disparate objects. Self-proclaimed “ontologist with a heuristic methodology,” Gabriel Rico pairs found, collected, and manufactured materials to create sculptures that invite viewers to reflect on the relationship between humans and our natural environment.

<TRACING>

Beijing Preservation, 2003

OMA

> The dilemma: building is less permanent in Asia and restoration often leads to a harsh reconstruction from zero that removes all traces of authenticity in favor of rigid, bloated rebuilding. In the name of preservation, the past is made unrecognizable.

> The most visionary approach to preservation would be to use it in a prospective rather than retrospective way by declaring different areas of the city to be preserved for different periods of time.

<PROJECTION & INTERVENTION>